Franklinton Brothers Lead Study Linking Pollution to Mental Health Struggles in Washington Parish

Published 12:00 pm Friday, May 2, 2025

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

SPECIAL TO THE DAILY NEWS

Two sons of Washington Parish are shining a national spotlight on the invisible toll pollution takes on the minds and bodies of rural communities like their own.

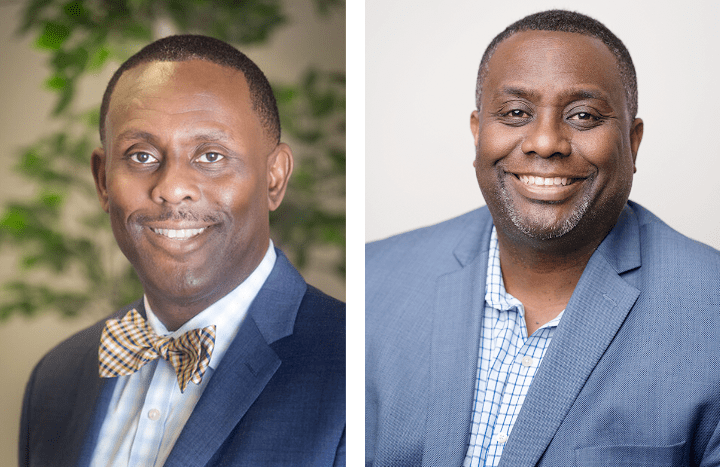

Dr. Delarious Stewart, a licensed mental health professional and professor at East Texas A&M University, and his brother, Dr. Kendric Stewart, an environmental scientist and senior administrator at Dillard University, have co-authored a new study that connects industrial pollution to increased rates of anxiety, depression, and chronic stress in Black and low-income communities across Washington Parish.

The study, recently published in the Journal of Wisdom Within Quarterly, uses local data and geographic analysis to show that residents in marginalized neighborhoods—particularly in Bogalusa and surrounding areas—live significantly closer to polluting industries than their wealthier or White counterparts. That proximity, they found, doesn’t just affect physical health—it’s deeply tied to psychological well-being.

“This is home for us,” said Dr. Delarious Stewart, a graduate of Franklinton High School. “We’re not outsiders writing about some far-off problem. We’re looking at the air our family breathes, the neighborhoods our friends live in, the places we were raised. And we’re asking: What’s the cost of living this close to environmental harm—and why does it keep falling on the same communities?”

Mapping the Stress: What the Study Found

Using a combination of Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) data and U.S. Census statistics, the research team analyzed how close different demographic groups live to known polluting facilities. The results were sobering:

• In predominantly Black neighborhoods, the average distance to a polluting facility was 1.2 miles, with 68% of residents living nearby.

• In predominantly White areas, that average distance was 2.8 miles, with just 24% living near a pollution source.

• Households below the poverty line also lived closer, averaging 1.3 miles from polluters, compared to 2.6 miles for higher-income families.

The Stewart brothers found that chronic exposure to polluted environments contributes to ongoing psychological stress, which in turn exacerbates mental health conditions like depression, anxiety, and trauma.

“When you’re constantly worried about the water you drink or the air your kids are breathing, it creates what we call toxic stress,” said Delarious. “And that stress builds up—especially when you feel like you have no way out.”

A Hard Choice: Health or a Paycheck

Nowhere is this tension more apparent than in Bogalusa, where industrial employers like the paper mill have long been economic lifelines—while also being linked to pollution events that impact air and water quality.

“People here have to make impossible choices,” said Kendric. “Do I keep a job that supports my family even if it might be harming my health? What happens if I speak up? It’s a tradeoff no one should have to make.”

This economic dependency, the study notes, deepens the psychological impact of pollution. Community members often feel trapped between survival and self-preservation. That pressure wears on families and feeds cycles of trauma, hopelessness, and poor mental health outcomes.

From Washington Parish to the National Stage

While the research is grounded in Washington Parish, its implications stretch far beyond. Communities across the South and rural America—especially those with large Black or low-income populations—face similar conditions. From the industrial corridors of Baton Rouge to factory-adjacent towns in East Texas and Alabama, the same patterns of placement and neglect repeat.

“Washington Parish is not the exception. It’s the example,” said Dr. Delarious Stewart. “This is a national problem with local roots.”

The study calls for policy changes at multiple levels. Recommendations include:

• Investing in trauma-informed, culturally competent mental health services in areas affected by environmental harm.

• Reforming zoning and land use laws to prevent further concentration of polluting industries near vulnerable populations.

• Creating economic alternatives so communities don’t have to choose between their health and their livelihood.

• Incorporating mental health assessments into environmental impact studies and public health decisions.

The authors also encourage community-led solutions, such as mental health education, local support networks, and advocacy training that empowers residents to speak out and organize for change.

‘We See You’: A Message to Their Hometown

The Stewart brothers say their motivation for the study goes far beyond research. It’s about honoring the people who raised them, giving voice to those who have long been ignored, and building a healthier future for the next generation.

“We didn’t write this for a journal or a grant,” said Delarious. “We wrote it for the people who live here, for the folks who feel forgotten. We see you. We hear you. And we believe you deserve better.”

They hope their work will spark meaningful conversations between residents, churches, schools, and local leaders—and inspire action at every level.

“We’re proud of where we’re from,” said Kendric. “And we want Washington Parish to be a place where people don’t have to sacrifice their peace of mind just to live and work. That starts by telling the truth—and by making change together.”

Sidebar: What You Can Do

• Learn more about local air and water quality through EPA’s Environmental Justice Screening Tool.

• Talk with your local elected officials about environmental protections and public health funding.

• If you or someone you know is struggling with anxiety, depression, or stress related to environmental issues, reach out to local mental health providers or community health centers for support.